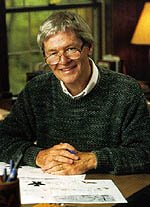

Johnny Hart was probably the second most revered cartoonist in my short list of artistic idols, right after Charles Schulz (Jim Henson is in a whole other category of worship).

Johnny Hart was probably the second most revered cartoonist in my short list of artistic idols, right after Charles Schulz (Jim Henson is in a whole other category of worship). As a kid, I’d be hunkered down on my grandma’s living room floor, trying and surprisingly succeeding to replicate Hart’s unique cartooning style, using Sunday comics and an old battered bargain basement collection of Hart’s early B.C. strips as reference. A slightly newer collection (newer for 1981, at least) of Hart’s Wizard of Id comics only strengthened my resolve to canonize the cartoonist. Ironically, the term canonize, to consider or treat as sacrosanct or holy, possesses such definition as to explain my decent from Hart appreciation as I grew older and came to distance myself from the man as did he from his readers.

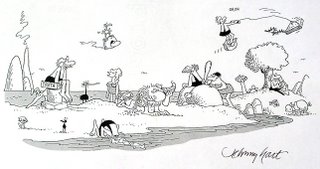

As a kid, I’d be hunkered down on my grandma’s living room floor, trying and surprisingly succeeding to replicate Hart’s unique cartooning style, using Sunday comics and an old battered bargain basement collection of Hart’s early B.C. strips as reference. A slightly newer collection (newer for 1981, at least) of Hart’s Wizard of Id comics only strengthened my resolve to canonize the cartoonist. Ironically, the term canonize, to consider or treat as sacrosanct or holy, possesses such definition as to explain my decent from Hart appreciation as I grew older and came to distance myself from the man as did he from his readers.The Hart I had known from my childhood was a brash and bawdy man of bar room burlesque, described to me through the previously mentioned dog-eared (and seemingly chewed) collection of B.C. strips. In those early days of Hart’s career, he showed us that the caveman invented the raunchy joke right alongside the wheel and fire.

But in 1977, as has been boastfully reprinted in countless religious publications, Hart found god.

So as to sidestep any misunderstanding, I stress that finding god isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Schulz had known god all his life, even so far as to having been a street corner evangelist in St. Paul prior to finding his cartoon calling. Schulz never lost touch with his religion prior to his comic strip success, and managed to subtly incorporate it into his cartooning without sacrificing his characters, content, or humor. The man who revered god in one Christmas special was equally adept at creating his own holiday icon in the Pagan-rooted celebration of Halloween.

Hart, however, proved incapable of such balance. Shedding his “sinful” past and offering up his work as a religious sacrifice, B.C. became a heavy-handed, pulpit-pounding Christian eulogy to a once genuinely funny comic strip. Lines were crossed that I couldn’t accept, and my readership, like that of countless others I’d read, was lost to Hart indefinitely.

In recent years, turning 30 brought forth the nostalgia of pre-1977 Hart for me. And though that weather-beaten tome of B.C. strips was as extinct as the characters within, the memories were still there, strengthened by a recent acquisition of vintage Arby’s collectible B.C. glasses. Soon I found myself going back to Hart, avoiding his content but paying full attention to his artistic style, as fresh and fun as the day he began the strip in 1959.

Of course, by the time this wave of nostalgia passed over me, Johnny Hart, age 76, passed away from me, dying, as all us cartoonists truly dream of though few but Charles Schulz have managed, at his faithful drawing board. In an equally all-too-appropriate ending, Hart died the day before Easter, wanting perhaps to touch base with the Christian significance without stepping on the toes of the Man himself.

Now the nostalgia falls cold upon me, like revisiting your old family home to find that it’s no longer yours, and knowing you can never truly return. Did I do Hart a disservice by abandoning he and his work rather than adapting myself to their evolution (or more appropriately, creationism)? And what does it say about me that I idolized a womanizing, hard living and harder playing cartoonist rather than the pious creator who preached sermons though his strips? These questions and more fill the void that is left by the passing of Johnny Hart, and in the end, the answer to it all is suddenly clear.

Johnny Hart was a cartoonist who chose his own path, and regardless of what anyone else thought of his decisions and creative product, produced work of the most personal nature to the best of his ability, attempting to satisfy and unwilling to justify to no one but himself, save for perhaps god. I couldn’t see that when I was younger. But I can see it now. And for that strength of conviction, and for a level of talent and dedication that never faltered, even to his dying day, the man is again worthy of my respect and admiration.

I just wish he were still around so that I could tell him.

No comments:

Post a Comment